The Five Aggregates and the Sutta on the No-Self

This article is an introductory summary of the teachings of Zen Master Thích Thông Triệt on the topic, mainly based on the oral teaching of Bhikkhuni Zen Master Thích Nữ Triệt Như given for the Fundamental Meditation Course. For a comprehensive in-depth understanding, the reader is encouraged to attend the complete nine-seminar teaching program and read the writings of Master Thích Thông Triệt that are being progressively translated into English.

The Sutta on the No-Self is the second sutta expounded by the Buddha after his enlightenment. The Buddha taught it to the five ascetic monks, led by Koṇḍañña (Pāli, or Kauṇḍinya in Sanskrit), with whom the Buddha used to practice. Together with the Sutta on the Four Noble Truths, it forms the Sutta of the Turning of the Dhamma Wheel. It is part of the Samyutta Nikāya “The Connected Discourses of the Buddha”, Anatta-Lakkhana Sutta, number 22.59. Upon listening to the Sutta on the No-Self, the five ascetic monks achieved the realization stage of an Arahat (Pāli, or Arhat in Sanskrit).

Summary

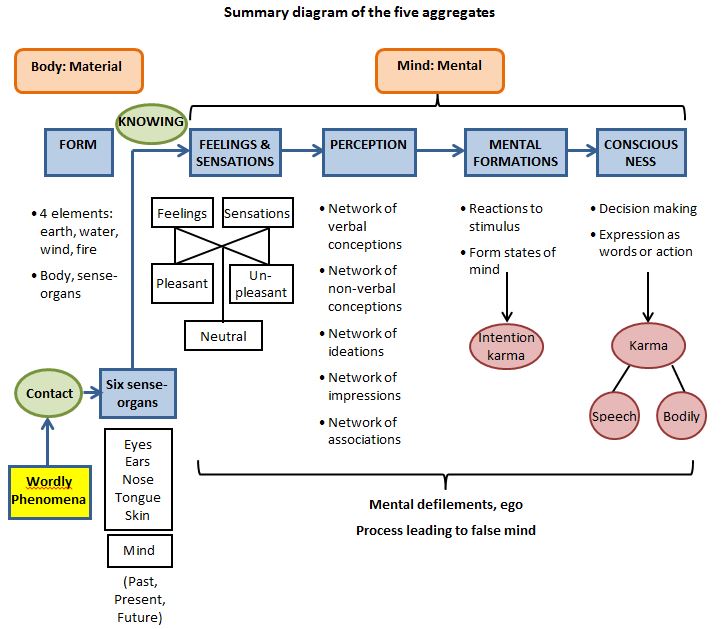

Aggregate is the English translation of the Pāli word khandha (or skandha in Sanskrit). A person is made up of five aggregates, the body (“form”), and the four aggregates of the mind: feelings and sensations, perception, mental formations, and consciousness. Underneath these aggregates are the egotistic self and its mental defilements that cause the person to cling to the phenomena of the world and be caught in them. Clinging and getting caught give rise to suffering in the unending cycle of deaths and rebirths. There is a pathway to ending the cycle of suffering and rebirths. If the five aggregates are still when we are in contact with external and internal phenomena, and there is no clinging from the ego, we dwell in our holy mind, or our wordless awareness mind. That mind is still, equanimous and joyful. It is objective, devoid of ego, compassionate and wise.

The five aggregates

The body (“form”) is made up of the four elements of earth, water, wind, and fire. The solid parts of our body such as our flesh, bones, organs, etc… are of the earth element. The fluids in our body such as our blood, saliva, urine, sweat, etc. are of the water element. Our breath is of the wind element. Heat in our body is of the fire element. The body also houses the five sense organs: eyes, ears, nose, tongue, skin. The Buddha also talked about a sixth sense organ, the mind-organ. The mind does not belong to the body, but does contact and receive information from the external and internal world like the other five sense organs. The mind also generates changes in feelings and sensations, perception, mental formations, and consciousness. While the other five bodily sense organs are limited in their reach, the mind has no limits. It can think of anything, can cross the limits of space and time. It is the most powerful of the six sense organs and powerfully influences our whole being.

When the six sense organs come into contact with the phenomena of the external world and internal world, the aggregates respond to the stimulation of the object. First the person experiences vague feelings and vague body sensations. These feelings and sensations are of three kinds: those that the person likes, dislikes, neither likes nor dislikes. These feelings and sensations transmit a signal to the person’s perception. At the perception stage, we have a clearer apprehension of the external stimuli. Perception comprises a diverse array of networks: a network of verbal conceptions, a network of non-verbal conceptions (e.g. gestures, movements), and a network of ideations (e.g. intentions), a network of impressions, and a network of associations. When we look at a plant and we say either aloud or silently in our head, “This is a beautiful bougainvillea”, we activate our network of verbal conceptions. When the teacher asks: “Do you understand”, and we nod our head, we activate our network of nonverbal conceptions. When we do our walking meditation and want to pick a beautiful flower, we activate our network of ideations. Impressions come from experiences in the past that left a profound mark in our mind. We see a snake and we shake: this is an example of an impression in our mind. When we feel the humid heat in Singapore and we remember the same humid heat in South Vietnam, our network of associations is activated.

These ideation networks create the inner talk and inner dialogue that are obstacles to establishing the samādhi state of meditation. Inner talk and inner dialogue constitute the worn pathway of language, an ingrained habit that we have established for many long years, if not many reincarnations.

Next come mental formations that are the reactions to the input from perception. Mental formations include states of mind such as sadness, joy, elation, anger, resentment, hatred, vengefulness, grief, etc… They are the white and black buffalo in the Zen Buddhism ‘herding the buffalo’ metaphor. The black buffalo refer to all the impure states of mind. The white buffalo refer to pure and equanimous states of mind devoid of egotistic self. Zen Master Thích Thông Triệt calls these mental formations the supermarket, the war zone. Mental formations transmit their signals to consciousness.

Consciousness investigates, compares, discriminates, and integrates all the incoming information. A decision will be made and expressed outwardly as words or actions. These cause speech karma and bodily karma. These types of karma are strong as they are intentional. However, karma has already begun when states of mind such as anger or hatred are formed. This is called intention karma.

How the False Mind is created

Underneath the five aggregates is the egotistic self with all its mental defilements, old habits, fetters, and underlying tendencies. Mental defilements are passions, infatuations, and addictions to worldly objects. The more we cling to objects or relationships, the more we get caught in them through attachment or repulsion, and the more sorrow we experience. Not able to be with the people we love is sorrow, forced to be with the people we dislike is sorrow, insatiable desire is sorrow. The Buddha talked about the five objects of desire: money, beautiful body, fame (and status, power), food, sleep (and rest). Not accepting change is also sorrow. The Buddha cited the main causes of sorrow as the four main categories of defilement: ignorance (or not knowing the path of spiritual practice and not practicing it), desires, craving for existence and false perspective. These four categories of defilement bring us back again and again on earth in the cycle of deaths and rebirths with the on-going sufferings caused by the desires of the egotistic self. When the ego operates underneath the five aggregates, our perspective is always dualistic, judgmental, emotional and subjective. Our perspective is corrupted by bias, prejudices, and fixed opinions. There is always the self and others. There is the attachment to, “I am right, you are wrong. I am virtuous, you are bad. You need to change according to my will, I don’t need to change. I blame you for all that is wrong, I am not at fault…” Under the influence of the ego, all five aggregates are activated and they react to stimuli with stressed body states, as well as disturbed feelings and sensations, perception, mental formations and consciousness. There cannot be peace in us, or peace in our relationships, or peace in the world with the self.

Impermanence and No-Self

Our body changes all the time. External phenomena change all the time. So do feelings and sensations, perception, mental formations and consciousness. As perception receives input from feelings and sensations, changes in feelings and sensations will generate changes in perception. Likewise, changes in perception will generate changes in mental formations and subsequently changes in consciousness. As a result, underneath all the five aggregates there is no solid core, no permanent substance, and no permanent entity. The Buddha said that the true nature of the aggregates and the self is emptiness. No-Self refers to the emptiness of the self.

The root cause of all our sorrows is that we believe that the self is real, permanent and unchanging. As a result, we believe in the reality and importance of our feelings and sensations, perception, mental formations and consciousness. The Buddha refers to it as clinging. When we believe that the self is real, we think that we are the self and we follow its desires. Instead of noticing that our mental formations generate anger toward our friend for lying to us, we feel “I am angry because my friend lies to me”. Living under the influence of the self, we are tossed in the dualistic waves of emotions: attachment and grief, love and hatred, happiness and sadness, etc. We compare and judge, falling into the trap of the dualistic mind: self and others, “I am good and you are bad”. Our views are corrupted by bias, prejudices, and fixed opinions. Our desires become insatiable, resulting in unending sufferings. Sorrow also occurs when we cannot accept changes. Sorrow arises when we are in conflict with other people or within ourselves (disharmony in our body, conflict between the aggregates). All conflicts come from the ego.

Spiritual practice

How do we get out of this vicious cycle of suffering? First we need to feel the urge to terminate our suffering. Then we need to find the right path and practice diligently. Phenomena of the world include objects, events, and our relationships with people, things and other sentient beings. If we can get in touch with the phenomena of the world and our internal phenomena without any word arising in our mind, without clinging, without getting caught, without getting attached or pushing the phenomena away, we have a clear awareness of what they are, just as they are. There is no response from our thinking mind, intellect, and consciousness. There are no thoughts, no emotions that arise in our mind. There is no interaction between our mind and phenomena from the external or internal world. Our mind is empty, completely still, at peace, immovable, equanimous. This is the wordless awareness mind, the still, holy mind.

When we open our eyes, in the first second, we can see everything and there are no words yet in our mind. This is the first flash of awareness of the wordless awareness mind. If we can maintain this wordless awareness, without clinging, all the five aggregates are still and the egotistic self is kept silent. There is no suffering, no karma generated in wordless awareness. The ego gets weakened further as we practice diligently. If wordless awareness is still fragile, we are in samatha. We are in samādhi when our wordless awareness is stable.

In wordless awareness, when someone praises us or puts us down, there is only hearing – just as it is. There is no naming, no labeling. In both cases, there are no words arising in our mind, there are no such things as: like, dislike, thoughts, emotions, or a decision to say something or to act on it in a reactive way. Yet we know how to respond effectively to what happened from the objective and intuitive wisdom of our wordless awareness mind. The wordless awareness mind is also endowed with the qualities of objectivity, benevolence, compassion, empathetic joy, equanimity and intuitive understanding and wisdom.

Looking at the five aggregates, feelings and sensations are the crossroads that lead the mind towards either peace or attachment. If we see, hear, touch things while keeping feelings and sensations still, our mind is at peace in a wordless state. Still feelings and sensations send a still signal to perception, mental formations, and consciousness. All of them stay silent and the ego is made silent. On the other hand, if feelings and sensations are aroused, they send a signal of like or dislike to perception, mental formations, and consciousness, which respond with their own reactions directed by the egotistic self. This is the pathway to conflict and sorrow.

It is up to us to choose to operate either in our worldly false mind with its suffering and unending cycle of deaths and rebirths or in our wordless awareness mind with its qualities of objectivity, benevolence, compassion, empathetic joy, equanimity, intuitive understanding, and wisdom. The Buddha encourages us to practice wordless awareness all day in the four positions, i.e. while walking, sitting, standing, and lying down. The Buddha calls this state of mind clear and full awareness mind (V: chánh niệm tỉnh giác). The sixth Chinese Zen patriarch, Hui Neng, calls this state “the great samādhi mind” (V: đại định), a state of stillness of mind that one does not enter nor exit, meaning that the mind is constantly in a state of complete samādhi stillness in wordless awareness while one is operating in the four positions.

Zen Master Thích Thông Triệt commented that even when we have achieved a deep solid samādhi state in our sitting meditation for twenty years, we are still not achieving an optimal outcome if we don’t practice in the four positions and if we have verbal chatter during those times. Meditation is about training our neurons to acquire a new habit of silent stillness. This can only be achieved by keeping verbal mental chatter silent all day to establish new networks of neuronal firing and new synapses.

![]()